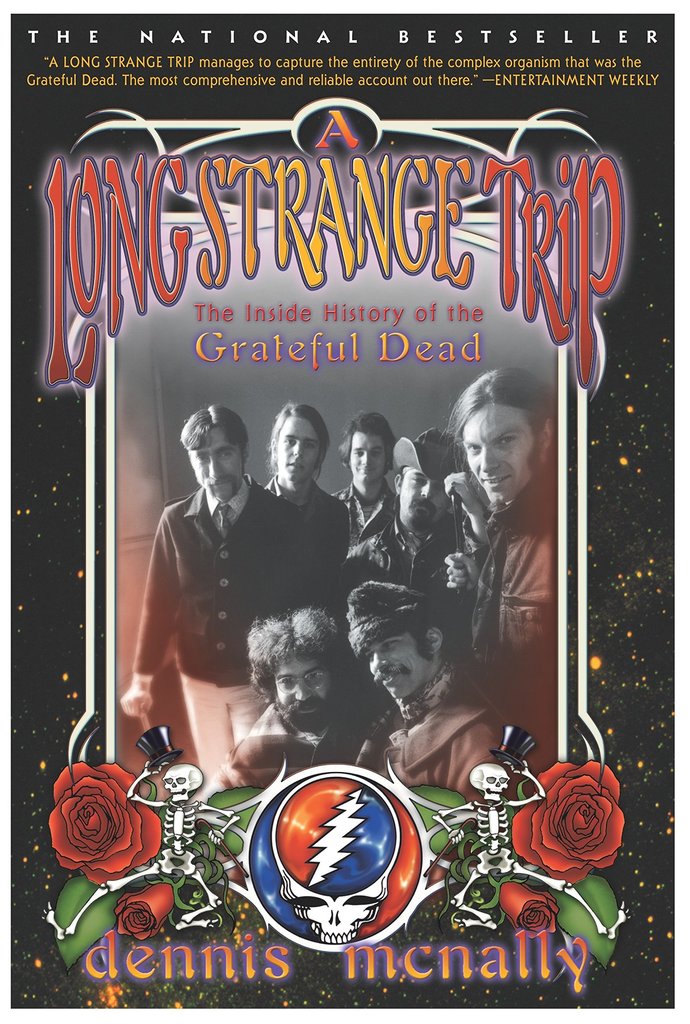

Dennis McNally, author of A Long Strange Trip and long time publicist for the Grateful Dead gave us a glimpse into how his relationship with the Dead began in the first of a two part interview prior to Jerry's birthday and the Days Between shows at The Hamilton.

Karin McLaughlin: Okay, so it's hard to find a starting point...

Dennis McNally: I am all over the place, aren’t I?

KM: So let's kind of give anyone who might be reading this interview a background if they aren't already aware - which is probably pretty hard, if they have enough of a piqued interest to be reading this - of who you are and what your history in regards to the music scene and specifically Grateful Dead is.

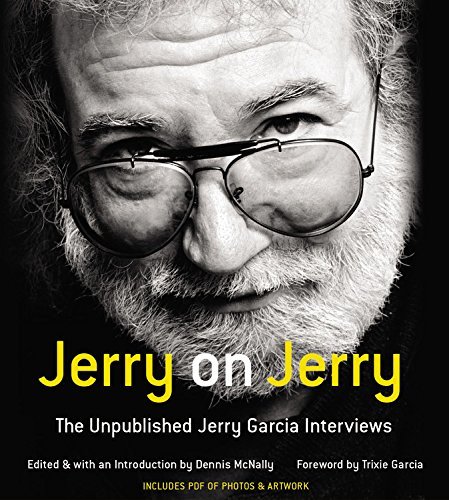

DM: Okay, well, I wrote the authorized history/biography of Grateful Dead called A Long Strange Trip, which came out in 2002. The reason I did that was because I had written a biography of Jack Kerouac that Jerry (Garcia) had liked and that was called Desolate Angel and, because of that, he had invited me to become the Grateful Dead’s biographer, bless him. I also wrote a history of American music and the relationship of black, African American music with white people, mostly young, white people, running from the 1840s to the 1960s and that was called On Highway 61. So I started with Kerouac and then I did Grateful Dead and then I went back and did all the background. Then, more recently, I was asked to put together the bulk of the interviews that I did with Jerry as part of the book research, in both a regular book and an audio book called Jerry on Jerry. I will hasten to add something that I don’t think ever got properly communicated by the publisher to the audience, which is - people when they hear 'audio book' they think, ‘Oh, well who read Jerry’s part?’ Well, Jerry did. These are the tapes of Jerry talking. He really was one of the best conversationalists there ever was and the fact that that didn't sell a million copies, I will go to my grave wondering about. Folks just didn't know and it's not too late, you can still buy this book, I’m sure on Amazon or wherever, Jerry on Jerry the audio book and you get, I think it's six CDs or something like that – I think it’s seven hours of Jerry schmoozing about almost everything. Save it for a good long drive and you find will find that that time goes by really fast (laughs) because, boy was he a good talker. So yeah, those are my credentials. Then in the middle of all that, I was hired by the Grateful Dead to be their publicist, which is why it took me 20 years to write the history of the Grateful Dead. I had to sort of put it on the shelf for a while. I was the Dead's publicist from well, on the road - the Grateful Dead publicist from 1984 to 1995, and then I was Grateful Dead Productions' publicist for another, pretty much, 10 years after that. Then I worked with RatDog for a while. I also have written a lot of the liner notes and whatever people asked me to do. So, yeah, that’s who I am.

KM: So when does the book on your life come out? I'm sure that's a great tale too (laughs)

DM: All the good parts, really are what I write about. You know, I very much enjoyed my life but, no, I’m a historian. I’ve done a bunch of lectures and tell the good stories, hopefully mostly funny ones, but the idea of doing a memoir, no. It takes a lot of energy to write a book and you need to love your subject. I find it very easy to brag about my clients, bragging about myself - I'm just not good at it. It boils down to an hour or a couple hours’ worth of good, funny stories and that’s not a book so I don't think that's gonna happen.

KM: Well never say never, right? You just need one of those like empowerment workshops to find some self-love and get you all gassed up on yourself and then you'll be ready to go (laughs).

DM: I’ll keep that in mind (laughs).

KM: So were you a writer that found a passion in music or were you a music lover that found a passion in writing?

DM: I have, not to ethnically stereotype, but I have what is frequently associated with the Irish -which I'm only one quarter anyway- but a way of storytelling that's always been part of my life. I wanted to be a historian, which was a formal way of being a storyteller, ever since I had a great history teacher in my junior year of high school. Then coincidentally, and with great, good fortunate - because I was a complete nitwit and chose my college for lots of reasons, but none of them the good ones, it turned out to have a fabulous history department. Then I went to graduate school and I picked it for lame reasons, and it turned out to have, not only a great history department, but it was as though it had been specifically designed for my needs. So the answer your question is really, I was a writer and started with Kerouac, but coincidentally and not so coincidentally -you know you believe in coincidences?

KM: Yeah, of course!

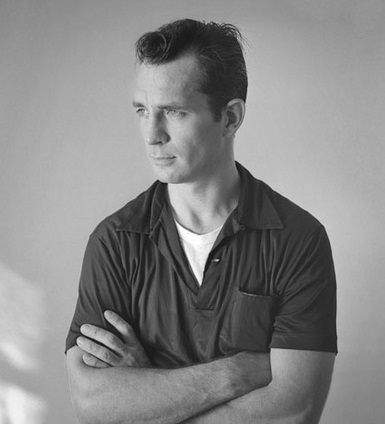

Jack Kerouac (c) Tom Palumbo, circa 1956. An early influence of Dennis McNally's

DM: The person who turned me on to Kerouac as a specific subject - I was sort of vaguely thinking ‘Maybe I’ll do the Beats’ while I was in grad school - he said, “No, no - do Kerouac, his papers are at Columbia and you can stay with my friends in the Bronx.” Now when you're a broke graduate student and somebody tells you ‘Yeah I got a free place for you to stay’ and it’s on the subway line, you think, ‘Whoa, that's a game changer!’ Again, coincidentally, or not, my folks had just, in that period, in the previous year, moved 10 miles from Kerouac’s hometown of Lowell. So the universe lined up and smacked me in the face and said, 'I think it's your duty to write about Kerouac.' Long story short, I did and the same guy that told me about Kerouac, took me to my first show. When we got there, he told me to open my mouth and stuck something in it and I had a wonderful time. He, like any good Dead Head, all he ever listened to was Grateful Dead and we spent a lot of time together, particularly in my first year of grad school, listening to a lot of Grateful Dead. I had always loved music but, as pretty much everybody in my generation, I mean now, you know, video games sell more, and to a lot of people are probably just as important, but when you grew up in the late 60s, you probably love music or loved it then anyway. So I became a Dead Head. Then as a historian, I quickly started realizing that there are all these connections between Kerouac and the Grateful Dead, most noticeably and obviously Neal Cassady, who is the hero of On The Road and of course was the avatar saint to the Grateful Dead and you know, Cowboy Neal at the wheel. So my very long winded way of answering a question is, I was a writer first, but then I found the perfect fusion of doing what you love by becoming that Grateful Dead's biographer.

KM: And you became a Dead Head by way of Jack Kerouac.

DM: Yeah, more or less. Kerouac and friendship. I mean all Dead Heads become Dead Heads because of some person in their life. Secretly a sibling most times, but this guy pretty much became my brother and said, ‘Hmmmm, you should listen to this’.

KM: That's funny we're talking about Kerouac, I just checked out from the library, which I think I'm just about only nerd that still uses our public library system, but I just checked out Dharma Bums, so I'm interested to read that.

DM: Oh, I highly, highly recommend it. I might add that as I get older, I'm giving away all my books and I love it. I'm one of the absolute triple black belt fans of the San Francisco Public Library and libraries in general. So, thank you for doing that. Coincidentally, I happen to be a Buddhist and, Dharma Bums is actually a very important book in the history of Buddhism in America. I’m not saying it's a masterpiece of literature, although I did think it was quite a wonderful book, but a lot of people started studying Buddhism because it was this popular success.

KM: Yeah, it's a very well-worn book. I can tell that a lot of people have read it.

DM: Yeah, absolutely.

KM: So what was, I mean, you said that, you know, it kind of had to be put on hold, and it was a long process, as far as organizing Long Strange Trip, what was the process as far as organizing the story or the flow of that book? How was that process and how difficult was it? What was it like? Or kind of just, can you give us maybe a little bit of insight into that?

DM: Oh, yeah, yes, I can, because it's kind of a great story. I can go on and on. The problem would be to tell it less than an hour (laughs) because it really was one of the two or three most remarkable moments of my life, I am not joking. You know, I got invited by Jerry in late 1980, to be the Dead's historian, and I was very happy. I started researching, starting with him and Phil's, because they were the oldest guys in the band and had had the most stuff happened to them prior to being in the Grateful Dead. I started digging around in the Bay Area folk scene and the College of San Mateo jazz band, and stuff like that for Phil. Over the next three years, I started interviewing people within the band and the larger band, because the band is not six guys, but about a hundred employees, or 50 employees, and 150 people you could call family. So I'm researching away, gathering up more and more information and at one point, I had thirty, three-ring binders of notes typed up. This is all in the early 80s. Then in 1984, I met my future, well, then future wife, still current wife, who was the first person on the block to get a Macintosh computer. Matter of fact, she was the person who taught Jerry how to run a Macintosh. They were buddies long before I got there - Jerry was our matchmaker. So then I looked at the computer and after fooling with it for a couple of months, I suddenly went, “Oh shit, I have to retype all these notes into the computer?!” So, that’s what I did. By the time I started writing, I was really glad I did. That's yet another of my typical diversions.

So I'd been working on the book for four years and I had lots and lots and lots of information. There was one, main technical problem which I could foresee and that was that I’m a big believer in chronology -you begin at the beginning and you end at the end. I didn't have an ending yet, but that was a side issue - I never did have an ending until Jerry died and I know that's another story. So the technical issue was this: there was the chronological narrative of events that I would write, and then there were also stacks and stacks and stacks of information that wasn't chronological, that was topical, Things like: how a show got set up, the relationship of the band and the crew, the office staff. This wasn’t just a band, it was and still is, remarkably enough, a subculture of this whole phenomenon. Dead Heads for instance. How was I gonna put all this together and get all that information in when it didn't necessarily have a chronological reference or didn't need to have a chronological reference?

Then, one day Healy, Dan Healy, who was the director of sound for the Grateful Dead, and lived in Garberville, which was about four hours north of San Francisco, asked me to get some tapes and get them up to his house. I was perfectly capable of taking them to the FedEx Office and shipping them off - I mean this was in the eighties - but I was looking for an excuse for a drive and that seemed like a perfectly good idea and just, you know let my mind unwind. So I took off, heading north on the 101 toward Garberville. Obviously, I've been thinking about this book and how I was going to organize it already for quite a while and something happened on the drive in which I suddenly understood how I was going to tell the story, which was in two streams. In one stream would be the chronological and the other would be, not a fictional, because every single fact was absolutely accurate as I had either observed it or I've been told by reliable source, but I could organize all this other stuff by depicting what was then a typical year in the life. "A Day in the Life" on Sgt Pepper, this would be a year in the life and it would start with January, when we’d have a company meeting and then end it with New Year’s Eve. You’d also have, in between, a Spring tour and a Summer tour, a Fall tour. Then you could depict certain songs, you know, the songs that I thought were really important and describe how they affected Deadheads or whatever. This all happened as I'm driving. Fortunately, thank God, I had a notebook and paper with me, although I did almost drove off the road a couple times. I put the paper on the steering wheel and started scribbling. Of course, I made a million changes after that, you know, moved the chess pieces around, but I defined the chessboard - or more like a jigsaw puzzle – but I defined the puzzle and the basic outline, the basic concept that I was going to have these two kinds of chapters. Originally it was three, but my editor at Random House said, ‘No, let’s not over complicate this’. So yeah, that's how it happened and boy was that a good day! As a writer, it was one of the two best days of my life. The other kind of similar thing that happened, also while driving -there's something about driving where your conscious mind has to focus, a large part of your mind is focused on the driving and being reasonably alert, but that frees up your subconscious and instead of daydreaming, if you've been thinking about something for a long time, it can stumble into great places. It certainly did for me both once on the Kerouac book and once on the Grateful Dead book.

KM: And then you end up driving somewhere you weren't planning on it, because you get so distracted. (laughs)

DM: Well, fortunately, there was only one road so as long as I stayed on the 101, I was in good shape. (laughs) So I got up there and delivered the tapes and pretty sure I spent the night and I drove back and then I had an outline. Once you have an outline – you need an outline and a first and a last sentence, and then you just fill in the blanks.

Jerry on Jerry by Dennis McNally

KM: There you go! And this is also another reason why we should all listen to Jerry on Jerry, the audio version, right? Because who knows what inspiration will happen in the car? So would you say, figuring out how you were going to, you know, make this book flow was kind of one of your biggest ‘aha’ moments of your life?

DM: Oh, absolutely. Oh, no, I'm not joking. That, as I say, those two moments, once for the Kerouac book and once for the Grateful Dead book were truly, truly important in my life as a writer. So that was in like, 1984 or 1985 and then, I might add, that right around that time - I tried doing both, that is being the publicist and being the biographer simultaneously for about six months. Now, other than the fact that you work - and I’m not asking anybody to whip out their handkerchiefs and cry for me, because you work for the Grateful Dead - it’s more than a full time job. It was a great job, the best I'll ever have, but it was like sixty hours a week and I'm talking about at home. On the road, it was much more than that. So the fact is that, I didn't have time to work on the book. Besides that, the point of view, as the publicist - I was an advocate - and as the biographer, I was trying to be fair minded and I’d say things in the book that are, you know, not necessarily complimentary. The word emotional cowardice comes up for instance, now and again, where they refuse to address issues because they just didn't have the guts to do it. But you know, we're human and fortunately, at least four of them still are human, as to say still alive right? The fact is that the two things didn't work. So I set it aside and I put a Jack Kerouac style little notebook in my back pocket so I could write down whenever anybody says something funny. A lot of the material is in those, I call them interludes, those other chapters, they came out of that notebook, because that's what I would witness. In a way, if I say so, one of the strengths of the book is not merely that it was a bigger story, since it was about the Grateful Dead, but it gave people an understanding about the way rock and roll worked. Things like trucks for example, and how important they are. The average person just doesn't know about stuff like that. They think, ‘Oh, you mean all those lights and sound equipment just got here?’ and they don't know how important that trucker is. So there's a there's a practical element to the book that came out of being on the road for all those years.

Dennis McNally with Jerry Garcia at the United Nations (c) Bob Minkin

KM: So let's talk about your transition from historian/book writer to publicist. I know you said that there was a period where you were doing both - and then you learned that you obviously couldn't do both, but how was that transition and kind of how your role changed and the dynamic even changed between you and members of the group members of the crew?

DM: Well, I spent, as I said, some three years as just a biographer before I got hired and in a sense that was my job interview. I didn't realize it at the time, but I spent those three years and I didn't piss off anybody too badly and people got to know me. So, what happened was that one day, Rock Skully has been the publicist and he had to take a long vacation to get himself together and one day at a company meeting the lady that answered the phones, Mary Jo said, ‘What are we gonna do about publicity? The media calls and nobody answers the calls or returns their calls and then they call back and nobody answers, what are we gonna do?’ and Jerry says, ‘Get McNally to do it, he knows that shit’, which was semi-true, in that, I had done a book tour for my Kerouac book. So I knew that a publicist contacted the media and said, ‘Say something nice about my client.’ To be honest, I haven't learned a goddamn thing since. I've been doing it for 30 years, and I do know more people but, you know, the principle, it's not rocket science and the principles remain the same.

So it changed my relationship. I mean, it changed my relationship a little bit, it deepened it because I became an employee. Now, Jerry once was told me that he was sort of impressed with me, I think he used the word ‘in awe’, which is embarrassing even to say, because he really, really, really - Kerouac was really important to him as a young man - as a 15 or 16 year old guy, it gave him a major sense of his personal identity. So I was this respected Kerouac guy. So it was different than the first time he met me, to be his employee, it's a different thing. On the other hand, I might add, that he was not in love with the idea of doing a million interviews and so I would pick and choose and again, didn't piss him off too much so he always said yes, thank God. But I also said no as needed.

I can only say that in 1986, when he went into his diabetic coma, Jerry - Phil and Mickey, to be honest, were very nervous, and, and they decided they really wanted to demonstrate that they were sort of in charge. So they immediately laid me off, I was the only person who got laid off because I was the new guy and then, in 1992 when Jerry got ill, they once again called me into the room except instead of laying me off this time, (laughs) they asked me for advice about how to deal with things. Because by then, I've been around long enough and I got some serious respect for the way I handle various things. I had learned a lot about how to be a publicist and what to say and when to say it. Then in 1995, when Jerry died, once again, I went into this room where the band was, except this time I said, ‘Does anybody want to make this announcement to the press with me?’ and they all went, ‘No, no, you can handle it.’ So you know, over the course of my time there I think I grew into the job. Certainly my relationship with the band grew such that that they trusted me and acknowledged that I was probably not gonna screw up too badly and should be left alone, which generally they did. It was an ideal job in many ways for me because it was self-directed and didn’t really have anybody looking over my shoulder, because I don't like being all that closely supervised. They thought I was ideal because, God knows there was a lot to do and a lot of it was invisible. Shortly after I got hired, I went to the band and said, ‘You know, you really should have me on the road with you’, which is expensive - we figured it cost probably close to $10,000 a week per person on the road.

KM: Wow!

Dennis McNally with the Grateful Dead (Photo Credit: Susana Millman)

DM: Hotel rooms, mode of transportation, per diem, etc. Members of the crew, all of them thought that any dollar not spent on members of the crew or the band, well, you know, was money stolen from their children's mouth. But, seriously, members of the crew said, ‘What do we need you for on the road? We've already sold the tickets!’ I said, ‘Well here's the deal - the Grateful Dead (this is 1984) is a story and I might add - it's not only a story, but it's a story that can be played either way. You've got CNN by then, which is 24 hours, which is just this giant hole of space and they need to fill the space with stories and they don't really care. There are times when they don't care whether the story is positive or negative. Now, if you welcome them into the show and you give them footage of the band, the lights and good music and give them a good look and good sound feed, then that'll be their story because they are inclined naturally towards a feel good story. They do enough bloody car wrecks, talking about local news too so they’re happy to do a feel good story.

If you don’t allow them to cover the story, particularly in places other than New York City, three blocks away from Madison Square Garden, where you couldn't tell if the Grateful Dead is in town or in Cincinnati where you see all these people in tie dye and they think, ‘We're being invaded by the hippies’, which is obviously a major story and they're going to cover it how they want. The point is, they could either do that and if they’re not allowed in, they will cover the mess in the parking lot – Dead Heads and just trash or the people selling a doses, doing doses and being indiscreet in whatever fashion. You can't always trust the local promoter to supply somebody to get a good story because they don't work for the band and they don't know. They just don't have the motivation that the person that is working for the band has.' That was my answer to the band and crew about why I should be on the road and that's why I was on the road for the next eleven years, because what I did was make the TV and the photographer's in particular, who could be the most obvious and potentially intrusive, I made them invisible. They came in and they went out. They didn't bother anybody, and most importantly they didn't bother the crew, which was responsible for keeping order on the stage. We had the TV out of the soundboard with a good sound feed and they would be warned - you need a good set of a tripods, you got it, they wanted to shoot the band straight on, we worked with them to grant their wishes and they were happy. Thanks to Dan Healy, they were happy technically and I kept them out of trouble so everybody's happy. This did lead occasionally, to a crew member saying, ‘Just what is it that you do around here?’ and I go, ‘Well, I just had four sets of film crews and seven photographers in here and you never saw them.’ They would go, ‘Really?’

KM: So you were a magician? (laughs)

DM: Yeah, on a good day!

KM: So, I mean, I can't even imagine the stories that you must have and how often you are caught telling a story or relating something to these times. I don’t know if, are you familiar with the Grateful Dead channel on Sirius XM - they always have people that call in and they call them the ‘Tales from the Golden Road’- I don't know if you listen to that station at all.

DM: Oh I've been on it.

KM: So I'm sure you have tons of great stories, tons some people probably wouldn't believe but are there, let's maybe say, certain things that stick out as times that – I mean obviously you are friends with everybody in the band and also as a publicist you kind of play two roles and it's two sides of the coin - are there sometimes that you hold very near and dear to your heart, that maybe might not be stories that you always share but just - I know you say you had the luxury of having one of the best jobs in the world - but something that when you look back you think, ‘That right there is what made everything worth it’? Or is it too hard to narrow down one specifically?

DM: Well the honest answer is yes, several million, yeah, but I'll tell you one story which I think kind of illustrates what you’re asking. My wife, Susana Millman - she's a fantastic photographer and did a book of her Grateful Dead photography and we went all around and sold them. So many people these days don't even get this reference because they are too young, but we did what we call a ‘Georgie and Gracie act’, if you've ever heard of George Burns and Gracie Allen. They were a comedic team in which Gracie would pretend to be slightly air headed and George would say these strange, funny, hilarious things and would punctuate this with these dry, very witty, straight answers. This is in her book too, because I wrote it - I wrote up three short essays- it's her book, I am only responsible for the punctuation.

I did write two or three very short pieces and one of them was about this one night in which we had the perfectly opposite experiences and that was the night that the Grateful Dead went to the Bammies. The Bammies was the Bay Area Music Awards -it was kind of a local, small scale, amateur hour version of the Grammys, and it was an excuse, in the eighties – there were a lot of great Bay Area bands -to pretend to be an adult and get dressed up and drink champagne, and celebrate. The Grateful Dead had put out "A Touch of Grey" and the album In The Dark and it was thought that they were going to win all the awards, which they did. I got a phone call from the magazine, BAM – Bay Area Music, who sponsored everything and they said, ‘Would the Grateful Dead come and play for the finale?’ For Susana - everybody in the band came, the families came, it was great. She was taking pictures everywhere. All the women in the office were there and their adult children, it was just a chance to really get an idea of what an amazing trip it really was. She had been around for a long time, but I had only been the publicist at that point for three years, four years and was still learning my way, I guess or feeling that I was. For her, it was a marvelous night - she got some great pictures - it was like a family album, a family night and that sensation really is what led her to eventually do this Grateful Dead photo book.

Dennis McNally with Bob Weir (c) Bob Minkin

So, she had a great time and I spent the night as uptight as I've ever been in my life, for the simple reason that Jerry didn't want to be there. There were two reasons, two fundamental reasons why that was – one was that the awards were awarded by voting competition. In other words, it was a competition and the concept of competition in music, to Jerry, was completely foreign. It’s why he didn't come to the to the Rock-n-Roll Hall of Fame – the whole thing that some make it and some don’t. Who’s in the club and who is not – that was not his idea at all. Now, on a more practical level, also because (at the Bammies) you had twenty bands or whatever it was, playing in the course of the night and you had to have a standardized setup. You just simply could not change over the stage. Now playing on somebody else's equipment was not Jerry Garcia's idea of fun. So he didn't want to come from the very first moment. Also, because it's not a money event, and we’re not being paid, suddenly I inherited it as a promotional event, which gave the tour manager the opportunity to say, ‘Have fun Dennis, not my problem, I’ve got enough to do!’ So I go to the band first and say, ‘Do you want to do this?’ and everybody says, ‘Sure, why not, absolutely.’ And Jerry said, ‘I don’t know man, I don't know.’ So I said, ‘Look, think of this as Noblesse oblige. These are your friends, your peers, the people that you've been with (this is 1988 now) the last 23 years of your life, the people in the Bay Area music community and they want to say congratulations, we love you. So, be kind - show up,’ and he said, ‘oh ok.’ It wasn't enthusiastic though, so I wasn't sure he was actually going to do it. The possibility that he would at the last second go, ‘You know, I just don't want to do it.’ Keep in mind that Jerry Garcia - there weren't many times in his life by then that he had to do something that he didn't want to do. He didn't go to the doctor because he didn’t want to and that’s why he died when he did, because he wouldn't go to the doctor - he just didn't want to go.

KM: Yeah, I don’t like going or really ever go either so I’m with Jerry on that one (laughs).

DM: Well, what happened was, in the end, he did show up and of course, he did play and it was charming as all hell and, you know, made it like it was the happiest day of his life. But the moment that made it all worthwhile for me was that I’m standing at the loading dock of the Civic Auditorium, waiting for him to show up and, sort of sweating blood. The van with him shows up and he gets out and I start breathing again and he comes up the steps and he looks at me and says, ‘You know, I just couldn't figure out a way to leave you holding the bag.’ And I went, ‘Thank you’ and it was like, the biggest compliment I ever got in some ways. He was a great boss by working under the assumption that you knew what you were doing and let’s all just get this done. He didn't spend a lot of time saying, ‘Great job!’ I might have gotten three compliments from him in my whole life but every day was a compliment because I felt his trust. So that was great. So yeah, that was a big one.

KM: That's a pretty good one. The fact that he respected you enough to do something that he probably didn't want to 100%.

DM: Yeah, because what I said was true - it was his whole community, you know? Come on, it's okay to be a curmudgeon but not this time.

KM: Oh, that's good. That is a good story. It’s a nice story, I like that one. Maybe we'll hear some party stories another time.